Prosymmetry recently published an interesting case study on improving portfolio management through better resource management. The key message of the case study was that choosing the wrong utilization rate upfront could have negative ramifications across the resource management function.

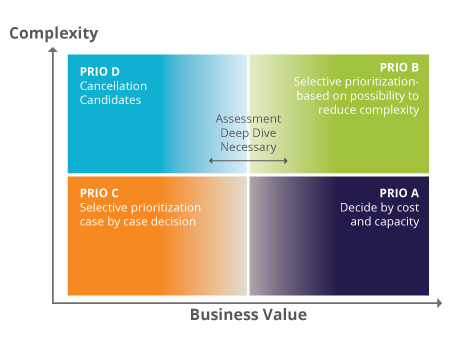

What caught my eye was a chart in the case study about how to analyze and prioritize the portfolio. The chart, shown below, lays out what is effectively a 5-quadrant model (where Deep Dive is the fifth quadrant).

We should do projects

Quadrant Priority C projects are the ones that the business units think of as quick wins for THEM. They aren’t, by definition, strategic, and they rarely have an easily provable business value. Since there are usually so many of them, I recommend that only about 15 to 25 percent of projects in this category deserve any serious consideration.

So, how do you determine which projects are worth evaluating? There are generally two cases. First, a specific business unit is struggling because one of its key systems no longer meets its needs, or second, there is a proposal that, in some manner, relates to employee welfare.

In the first case, very little analysis will be required. Generally, you simply need to look for excessive overtime or low employee morale related to the system. In the second case, it’s typically underspending on employee-related issues.

Kaplan and Norton would have classified the latter issues as “learning and growth projects” in their balanced scorecard approach. While these projects have always been important for a company to fund, we would suggest they are even more important now in our post-covid world.

Cancellation Candidates

Moving up the left-hand side of this model, the next quadrant is labeled “Cancellation Candidates.” I think this is utterly brilliant. After all, every organization has projects they need to cancel, but in most cases, simply don’t.

During the ten years I was at Gartner, I ran an informal poll on project cancellation. Whenever it was appropriate to the conversation, I asked clients if they thought their organization was good at cancelling projects. Only about 10% of the people I asked replied in the affirmative.

There are many reasons other than overt failure to cancel a project. The majority of projects that I’ve observed have simply under-delivered while at the same time continuously pushed out their end date in the hope that someone at some time would say enough.

Quadrant Priority D offers organizations an easy way to routinely enforce end dates. While each organization will have to tailor a rule to fit their circumstances, I recommend adding any project that is more than 90 days past the original end date to Quadrant D and insisting that they rejustify their future funding. By doing this as part of the portfolio process, it becomes very clear what the alternative uses for any funding might be.

The other category of projects in this quadrant are projects that are failing to deliver the hoped-for results. I’ve repeatedly seen changes in market conditions or technology turn a project from a good idea to a potentially very costly mistake. No matter how often we repeatedly warn about sunk costs, organizations without a framework like “Cancellation Candidates” to force the decision let zombie projects run to their natural conclusion.

The only exception to this rule is the project that can salvage value by changing either scope or direction. The important question here is: “is it worth it?” which is why there is a zone of assessment for this category.

Quick Wins

Quadrant Priority A projects are labeled as quick wins, but even here, funding is not assured. All too often, because of poor initial planning, a project can be neither quick nor a win.

For this quadrant, we recommend using a strategic roadmap to help guide the decision-making. The average organization has between 3 and 5 strategies, and within each of these strategies, there is a natural order in which the work can and should be done.

In this category, the critical issue is timing.

Ask the following four questions about every project in this category:

- Why is this project being done now?

- What will be the impact of doing this project later?

- At what point in the future would it no longer make sense to do this project?

- How can this project be broken down into phases in order to provide future go-no-go decision points?

I can guarantee you’ll be surprised at how many projects that are demanding to start on January 1st can be pushed out to a much later date with absolutely no negative impact.

Eliminate Complexity

Our last section contains the high business value, high complexity Quadrant Priority B projects. All projects in this category are effectively high-risk (another way of saying “high-complexity”). The goal with this category is to figure out how to reduce some of the complexity and/or risk.

In its most simplistic form, I recommend coming up with a complexity factor model. I listed nine possible factors you might consider, but these should definitely be tailored to your specific circumstances:

- Ambiguity – no agreement

- Too few resources

- Not the right resources

- Unfamiliar technology

- Too much work for the schedule

- Poor sponsorship

- Excessive uncertainty – politics

- Poor understanding of risk

- Competing priorities

Once you’ve made your list, give each factor a score. Then, try to figure out what—if anything—can be done to reduce the number you’ve assigned. This exercise is generally done by a team of people who understand what the project is intended to do and, where applicable, its underlying technology.

If the answer is still unclear, don’t try to force it. Time tends to make things that are cloudy more obvious, so if you’re unsure of the right answer, taking a step back can be the right next move.

I once worked on one project that was a top strategic priority, but we couldn’t reduce the complexity factors, so we chose to postpone a year. It turned out to be the right move — the emerging-market we’d hoped to penetrate never materialized.

Simple models – big results

Organizations with extensive experience and high levels of maturity will all develop the equivalent of these models themselves. For less-experienced organizations, using this model as an evaluation tool to improve your portfolio management is guaranteed to save you both time and money.

You don’t need perfection. Rather, your goal should be to incrementally adopt as much of the reasoning behind this model as is appropriate to your circumstances.