Every time we develop a new way to think about the work we do, we also introduce the same problems we are trying to fix.

In the past, a project was supposed to deliver a completed “product of the project.” Now, an agile undertaking is supposed to deliver an outcome. An outcome sounds a little bit more like a changed state to me than a product, but depending on what the goal was in the first place, both terms can be equally correct. The problem is neither term—product or outcome, or even completed scope if you go further back—speak directly to delivering measurable value.

Looking at the multiple sides of value

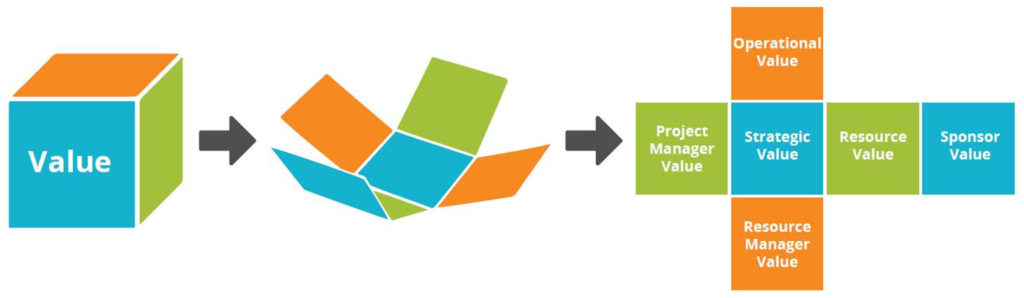

Luckily, defining value at the beginning of a planned body of work is easy if you use a value cube. It occurred to me one day that no undertaking ever has a single value measure. In fact, everyone who participates in creating the outcome, or using the outcome, or funding the outcome, has something they want to receive at the conclusion. If this is true, why shouldn’t we plan for it so we can measure it at the conclusion and be sure we have achieved success?

The value cube shown below is my attempt to visualize the multivariate nature of value. The definitions you use to label each face of the cube are completely at your discretion. The cube I’m showing here is intended to be a little bit more general purpose.

Focus on value to end customer first.

Where do you start? Each one of these faces can be assigned a group for which the project will deliver value.

Moving left to right, I generally recommend starting with value to the customer. If possible, try to define this first cube face in terms of value to the end customer rather than an internal customer. Senior managers and thought leaders always lament that employees look inward to define their success metrics, but I think it’s just a matter of learned behavior.

I must admit that I stumbled across the value of looking outward toward the ultimate customer in a meeting with a client. When I was managing a team of developers who did custom software development, a client asked us if we could develop a dashboard that took a multitude of data fields from a CRM system and made them visible on a single screen. We assured the client that we could, and I distinctly remember thinking at that moment that it was nice that the manager wanted to make life easier for his employees.

It was at that point that my brain kicked into gear. I knew beyond a doubt that altruism was not the motive for the project, so I asked the client why he wanted it done. At this point, his entire demeanor changed, and he smiled as he shared that he’d come up with a new way to increase revenue for his company. He managed a credit card call center, and he’d discovered that customers were happy if an issue could be resolved in 5 minutes or less. The new CRM system his company had just implemented made the 5-minute call completion a reality, but the multiple screen problem meant a call was still taking longer than it had to. A customer service agent currently had to flip between up to 5 screens to answer the customer’s question. If they could reduce that time to fix the problem to 2 or 3 minutes by having all the information on one screen, he hoped that customers would be willing to listen to a brief offer for additional credit card services, which would ultimately generate more revenue.

I was horrified when I realized I’d almost made a very serious but common mistake. I had taken the client at face value when he told me what he wanted. In reality, we would have delivered all the information on one screen, only to find out that the one screen decreased readability, which would have increased the time it took a customer service agent to resolve a problem.

By putting the most needed information on the front screen and information that wasn’t commonly needed on the second screen, we were able to meet the desired performance goal.

Then focus on value to your stakeholders

The next two boxes are generally some variation of sponsor value and team value. Sponsor value is an often neglected but critical value component. On one program I ran, the sponsor had a very large bonus riding on our on-time delivery. I made sure that even though we had to get a little creative in our definition of done, we made the agreed-upon milestone by the agreed-upon date.

Team value is even more subjective. I’ve run projects where the team wanted to be the first to use a new technology or to build something that would be new and exciting. I’ve also run projects where just enjoying their work because we had a great team environment was value enough.

For this blog, I’ve labeled the other two boxes time and money. Time and money are things that senior managers say they value but often don’t in practice. Value boxes should reflect the value that the company wants to maximize and not just things we are told we should be focused on (and yes, I’ve managed programs where money wasn’t that important and even time was secondary to success.)

The value cube is a quick shorthand approach to ensure that the outcomes we deliver aren’t a string of low-value check marks and are instead the best outcomes we can create for the broadest group of stakeholders.