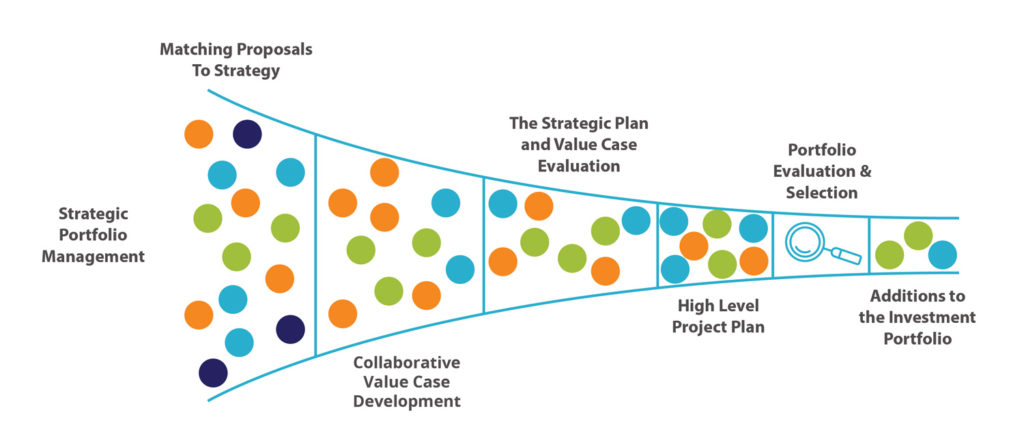

In my last blog, I discussed how to use a strategy matrix to evaluate the roadmap and initial proposal documents that all the business units have submitted for review. To recap, assuming the business units submitted most of their new investment proposals on their roadmaps, you should have visibility of two things: first, an aggregated timeline, and second, the strategic initiative and solution approach that every proposal aligns to.

Selecting investment options

Obviously, at this point, there is generally more demand than can be executed. The most common solution is to include everything in the portfolio and leave it for executives to sort it out themselves. Given that this ALWAYS results in more investments (projects or products) being included in the portfolio than there are people to do the work, we strongly recommend against adopting this practice.

What’s the alternative?

We would suggest reducing your list to only those investments that need to start in the next quarter or the next two quarters, whichever is more appropriate. If this idea makes your management nervous, then update your strategy matrix. Use one color for all the investment options that have passed the strategy gate and another color for any investment that should potentially be started in the next quarter or the next half.

How do you decide which investment needs to start right away? At least part of the answer should already be clear based on the business unit roadmaps, but if not, use our favorite technique we call “real-options light.” Ask the same three questions of every requestor:

- Why is this investment being requested now?

- What will be the impact of making this investment later?

- At what point in the future would it no longer make sense to do this project/product?

- How can this project/product be broken down into phases to provide future go-no-go decision points?

Once you have answered these questions for any investment whose timing isn’t crystal clear, the next step is to kick-off the collaborative value case process. Before we go into the value case in some depth we want to pass along a new technique for staying organized while you are winnowing the portfolio pipe line.

Using a Portfolio Kanban to stay organized

Having done more quarterly portfolio cycles than we care to admit, one of the annoying aspects of the work was being unable to share the status of the process with management in a visual format. Why visual? Because when you can show senior management something, they generally will tell you such things, as “don’t worry about this investment, I’ve already gotten agreement to kill it.” Or “don’t worry about this investment, we decided in last weeks meeting to push it to the head of the list.”

Adopting the practice of using a portfolio kanban at this stage solves the problem of more visibility. We know of one company that puts all the projects scheduled to finish during the quarter in the done column, the projects that are generally agreed to be under consider in the working-on column. The next- in-queue column is reserved for those projects that are in the process of preparing a collaborative value case.

Collaborative Value Case

A collaborative value case is NOT a business case. Its fundamental purpose is to gain support and alignment of goals between various business units.

After decades of doing portfolio management, we’ve found that most investment proposals are over-blown in their requirements. For companies who truly want to be more agile, it needs to become a point of pride to figure out how to solve a problem as quickly, cheaply, and creatively as possible.

The structure of a collaborative value case is very simple. Get five to eight people from different functional areas (usually IT, Finance, the requesting organization, and another involved organization) to discuss the problem and how the problem can be solved.

The cross-functional nature of the participants is critical. For at least the last two decades (ever since Y2K), organizations made an implicit assumption that the best way to solve most problems is through technology. Given this, the only time most business units collaborate is when an IT project (or senior management) requires them to work together.

A collaborative value case meeting breaks down the silos and identifies stakeholders who might have some thoughts on what the real problem is and how it might be solved by asking the following questions:

- Why is there a critical need to improve the current situation now?

- What improvements are necessary or possible? (Key stakeholders must agree to these improvements, which become the investment objectives.)

- What is the estimated cost the group is willing to invest to achieve the outcome? (Note: if the cost estimate at a later date exceeds this estimate, then the project is canceled.)

- What benefits will be realized by each stakeholder if the investment objectives are achieved? How will each benefit be measured?

- What changes are needed to achieve each benefit? (The key to realizing benefits is identifying explicit links between each benefit and required changes.)

- Who will be responsible for ensuring that each change is successfully made?

- How and when can the identified changes be made? (Note these changes can be process, staffing, new products, or technology changes.)

An Example of a failed project proposal (and a positive outcome)

We worked with one organization where purchasing, finance, IT, and two people from the shipping department came together to discuss why they needed to buy a new tool for reporting month-end data from the shipping department.

The project’s cost was estimated to be 45k, which would result in saving one person-day per month based on eliminating the current excel spreadsheet, which already contained all the relevant information. At this point, we were 20 minutes into the 4-hour meeting, and then someone asked, “why was this even proposed?”

The answer was illuminating. The software was proposed because the real solution would require that people (unionized shipping staff) have a whole heart-to-heart with people in management about their grievances. Bottom line, nobody wanted to admit they had a “labor” problem.

The rest of the meeting was spent discussing how it might convey the right information to management. The representative from shipping agreed to go back and speak with more of his coworkers to see if they might make some recommendations, short of formal union negotiations. The representatives from finance and purchasing also offered to see if they could find any way to make this issue more visible in their channels, and the meeting ended on an upbeat note.

Collaboration over paperwork

The collaborative value case’s real value is that it builds a culture of collaboration over paperwork (the old process of building a business case). Not everything requires a formal project. In a future blog, we will discuss how to use OKRs as a tool for tracking problem solving and change-oriented work instead of always relying on project management’s formal structures.

In our next blog, we’ll discuss how to examine all the proposed investments in light of their contribution to strategy.